The earliest inspiration for Kate Toledo scarves was a lush Grayson Perry carré that accompanied his 2011 exhibition ‘The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman’ at the British Museum. This artist scarf is a zingy, semiotic 90 by 90 cm silk map of the BM itself and was on sale at the exit for around £80

One can easily be a little wary of the relationship between instiutions and their giftshops. Rachel Dedman puts the connundrum best in her article ‘The Museum as Giftshop’:

Just as the museum’s narratives constitute fractional versions of historical representation, the giftshop’s effect on product is ultimately reductive: revolving around reproduction, a process that requires minutuarisation, shrinking paintings into postcards, sculptures into key rings, and flattening images to wrap around mugs and plaster onto iPhone covers

Bought – as this certainly was – in a museum gift shop, we would argue there’s a subtle yet important distinction in the Grayson Perry scarf. It was conceived by the artist as an object in its own right -a map no less!- totally analogous to the whole exhibition’s idea of a museum as pilgrimage destination, and therefore completing the exhibition, we reckon, not simply reproducing a work to echo and monetize the blockbuster.1

The Artist Scarf in the 20th Century

Rewinding a bit, the twentieth century history of art in textiles is rich, in more ways than one. It arose from the ever-pupular populist ‘art for the masses’ mentality, it sought to emphasize and embelish the everyday lives of ordinary citizens and, naturally, this turned out to be an extremely sexy and profitable business model for mill owners. In fact, artist scarves were a veritable twentieth century fashion staple on either side of the Atlantic, some of the most remarkable collaborations coming out of a post-war accessory trend established by one Zika Ascher, though of course the tradition pre-dates him.

Zika’s cousin Enda Ascher, it is said, was a lifelong friend of André Derain and George Braque. Through this famed circle of Parisian power-pals and artists, Zika Ascher was introduced to Picasso, thrillingly enough. Though Picasso initially resisted the artist scarf initiative, he introduced Ascher to Antoní Clavé and a whole group of spanish artists who collaborated on some of our favourite designs. Only eventually, in 1950, was a Picasso design printed by Ascher, and it was for the ICA. Despite his initial resistance, Picasso would later go onto collaborate with New York-based Fuller Fabrics where he created a whole range of prints. If you have 26 and a half minutes to spare there’s a great little documentary on youtube about Fuller fabrics’ relationship to the “Masters”

Ascher meanwhile, having founded Asher Artist Squares, created around him a vast network which connected some of modernity’s most important artists; this interconnectivity is still an essential point in the brand’s ethos and you can explore it in depth on their website. Lucien Freud’s artist scarf, for instance, is connected within the Ascher ‘network’ to other designs by English artists such as Robert Macbryde, partner Robert Colquhoun, and John Tunnard.

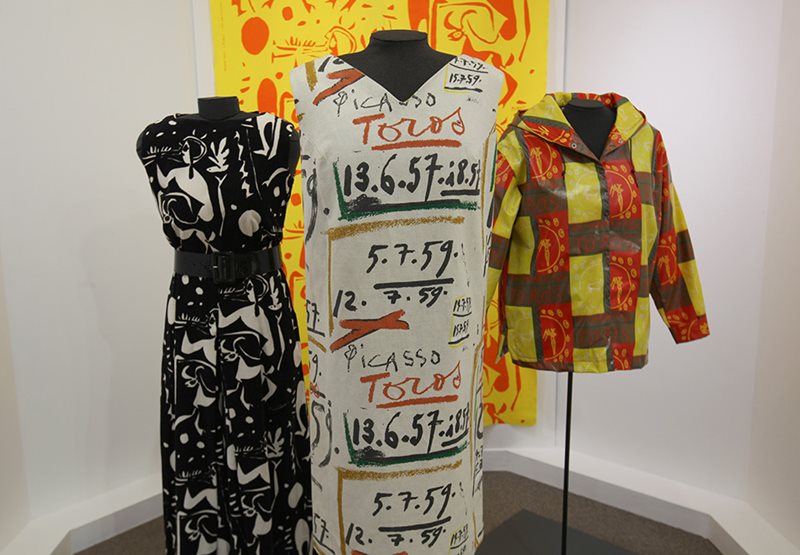

From the Artist Scarf to Artist Textiles

In 2015, the Fashion and Textile Museum in London held a major, touring international exhibition – Artist Textiles: Picasso to Warhol– dealing with the very blending of these distinctions between fine art and design. The exhibit’s central conceit (as always) is that, in working with textiles, artists such as Picasso, Dufy, Dalí, Delaunay, Chagall et al, were seeking to be less elitist, more accessible, more personal and intimate in engaging with clothing and home furnishings. It’s sort of ironic- if totally unsurprising – to see these now become exclusive collectors items: a seashore artist scarf designed by Matisse fetched £3m at Christe’s in 2011! The commercialization of artists and textiles was full blown by the mid ’50s ( ‘Art by the Yard’ by Jean Miró!) leading into the famous two-step pop-bop of art and mass production of 1960s. Easy as it may be to sniff righteously at this commercialization, the exhibition catalogue makes the convincing point that this fecund fad truly enhanced the prestige and appreciation of textile design as a medium of artistic expression. We sure hope so!

written by Isabella Toledo

- Worth reading/listening to is Grayson Perry’s Playing to the Gallery Reith Lectures where he discusses, among many things, his relationship to popularity and the mainstream: “If Linda Snell is a fan of contemporary art, then the game is won, it is no longer a little backwater cult.” [↩]